A recent KPMG report showed a seven-fold increase in the number of startups in India in the last decade. With eight startups entering the unicorn club last year and a few startups like OLA tapping the global markets, the landscape of startup has become stronger and more interesting. We invited Tarun Davda, Managing Director of Matrix Partners; and Ashish Kumar, Partner at Fundamentum Partnership, to tell us what they look for in a consumer internet company while investing. The panel was moderated by Narsimha Reddy, CFO at MoEngage.

We bring you excerpts from the discussion.

To begin with, we would like to know what are the exact growth prospects you look at? Where do you focus on your investments?

Tarun: We invest from seed to Series B. At seed, there is team and idea as there are hardly any metrics available in these cases. At Series A, when you are looking to invest, we typically look at early PMF. Early PMF depends upon the vertical you are present in and what business you are doing. The definition of early PMF changes from company to company. For an enterprise company it would be – do you have 5 to 10 sticky customers who are willing to pay you, who like your product, and are likely to renew?

For an early stage consumer company, it could be, do you have a few thousand users who are hooked on to your platform? At Series B, you move on to scalable PMF. The question then changes to, can these 5-10 customers become hundreds of customers? Not that you need to have them that day, but you need to foresee the scalability in the go-to-market and the sales engine that the team has built to be able to get to that stage. For a consumer company, we look at cohorts, retention and a bunch of other metrics. The series C is very simple – we check if the PMF is profitable, i.e., is the business model finally working? Is the contribution positive? Are you able to scale?

So, at a macro level, we start with the team plus idea and think all the way up to profitable PMF. For series A and B, let’s take an example of a content media company; a lot of people look at DAU. DAU is a good metric, but it can be bought or faked. One thing that can’t be fake is engagement. Engagement is defined by the amount of time spent on the app, and the retention, i.e., how frequently does one come back to the app. This is much harder to buy. So as an inventor when I look at the metrics of a company, the question I ask myself is which of these can be bought vs. cannot be bought.

When you look at the headline metric such as vanity, you also look at the sanity metrics, which defines the true stickiness on the platform.

Ashish: When we enter, we check if the product has attained a product market, for us to look at it. We call it Series B and Series C. We have typically identified two types of companies – one is where we see the company reaching near profitability. When I say near profitability, I mean that I anticipate the company to become profitable in the next 2-5 years. Usually, in a country like ours, these will be in domains and business models where it is not a winner-take-all business. The second type of business is the winner-take-all business because of the type of market or product they have.

The metrics for both businesses are very different. As an investor and an entrepreneur, it is important to know which market and which classification are you chasing. When I talk about potential winner-take-all businesses, I look at two large metrics. One is whether the market share is increasing or not. For example, let’s take the online retail or transportation business. You know online retail will be an x percent of the total market, which is growing at a particular pace. It could be 10%, 12%, or 15%. Now, when you look at an online retailer, you will know what your growth in market share is and is that growth faster against your competitors or not. Fundamentally, if it is a winner-take-all business, it should be on the positive side.

The second metric I look at is, is your unit economics improving? I am not saying it has to be positive unit economics. That’s a rarity in a country like ours. However, if you are growing your market share and if the unit economics is improving, that is a business that will ultimately win. It is just a matter of time. That is how we look at companies which can be a winner-take-all business. The market share becomes a growth metric when the market and segment to which the business belongs allows you to have multiple companies in that segment. The growth will be measured by how much you are growing per year.

The benchmark will be, are there multiple players, are you and your value determined by how fast you are growing, do you have something which could help you grow greater than the benchmark? The benchmark could be 50% Year-on-Year or 100% Year-on-Year, you should grow faster than that. The second clearly will be improving unit economics.

I would like to dig into it deeper. Could you please give examples of the companies you are associated with? What metrics do you see in successful companies?

Tarun: Let me give you two examples. One, I’ll take a consumer internet company like OLA. There’s a reason why we invested in OLA as opposed to other hyper-local delivery companies. Fundamentally, the first question anyone looks at is what is the total addressable market and is that a large opportunity. Let’s keep those aside. I think the metrics we looked for OLA were – first, the gross number of rides that are being fulfilled every day; second, in the early days we looked closely at stock-outs which is, how many times did a customer open the app and not see a cab available in their area. To us, that was a proxy to demand. When we invested in OLA, our thesis was that this is an unconstrained demand market.

The question is, how do we measure that on a daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly basis as an investor if the demand was unconstrained. Today, that metric is less relevant because there is more supply. However, what we were seeing is whether there is money to be made. Maybe that is not happening today, but if I go from Point A to Point B if I take out driver fee, fuel, and maintenance, it is still a contribution positive industry. Now what we start looking for in those businesses is the top-line metrics, what is the take rate you can charge, which is a very key metric in terms of net revenue.

Once you take that take rate and net revenue, from that essentially as a company, there were three large pools of cost. One pool of cost was how much you are spending on discounts because it is imperative to give discounts in the early days. Today a lot of people complain that the discounts aren’t as much as they used to be but what percentage of your take rate is being plowed back into the discounts? The second one is what percentage of your take rate is being plowed back in terms of your driver incentives. The third one was payment processing costs. Now, for an extended period, this number used to be negative for all the cab aggregator companies. Somehow, last year, we turned the contribution to positive at OLA. We took out all our incentives, discounts and payment processing costs from our take rate and found it to be contribution positive.

Today, the company is at a stage where we have started to look at much more mature company metrics like EBIDTA, break-even, and ROCE. That’s at the financial level. On the operating level, it’s very about how efficiently are the companies able to match demand-supply like, what is the average wait time. The biggest reason why OLA or UBER was successful globally was they cracked this golden metric, which is customers will stick if the average wait time is 4 to 5 minutes. Average wait time made a big difference in the customer retention cohort. If the app shows the cab to be 10-15 minutes away, there are fewer chances they would depend on an OLA the next time as compared to the customer who saw a wait time of 3-5 mins.

So, the average wait time was a critical metric. The last metric was cohorts- what percentage of customers acquired in month one are making a booking in month 2, 3 and 4. Within cohorts also, most smart investors will not look at only customer cohorts. They will look at ride cohort and revenue cohort. The last one is the pricing lever where we intelligently use data science to figure out who can pay a little more so we can charge them according to that. In investor parlance, what we typically look for is a ‘smiley.’ You may want to start with ‘x’ number of customers, and there will be some decay. However, eventually, the really sticky ones become so hooked on to your platform that the revenue cohort becomes like a smiley.

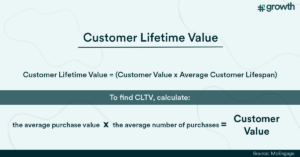

A SaaS company is slightly different. The most important is that what is your volume churn. What is your value? Are you able to make more money per customer? The golden rule for a SaaS company is if you have 100 customers that pay you $100, next year, maybe there is a churn of 10-15%, so there are 85-90 customers left. So out of those 85-90 customers are you able to make $85-90 and can you potentially make $120, which is your net revenue churn? The best SaaS companies that we have seen are those that continue to grow and end up having a negative net revenue churn. That means by doing nothing; they are able to grow 10, 20, 30% Year-on-Year. The next metric we look at is the customer payback period.

In every business, the enterprise sales cycle tend to be very long. It takes anywhere from four to nine months depending on which company you look at and the size of the deal. One thing we look at is that how much time, effort, energy, and dollars were taken to acquire this customer and based on your gross margins and based on your customer retention, which is the LTV cap, how long does it take for us to recover the investment that we have made in each customer. The benchmark is that the best companies have an LTV cap which is more than 5x. So, if you have a 70-75% growth margin in enterprise services, it will translate into customer payback within nine -12 months.

Not all companies get there, but that is generally what an investor will look for in a SaaS business. The last one would be T3D2, which is basically you want to see triple growth in the first three years and double growth for the year after that. So, if you start with million dollar revenue, can you grow 3x in those three years and then grow double after that? The most successful SaaS companies have shown all these growth trend lines and have shown net negative revenue churn and have shown short customer payback in less than 12 months, more than 5x, sometimes 10x LTV cap.

It all eventually boils down to capital efficiency. How many dollars you took to create x dollars. Unfortunately, in India, companies burn $1 to generate $1 in GMV whereas globally companies generate $10 in GMV by burning $1. Broadly, all these metrics are proxies and what you eventually look at is ROCE. At every point, we look at capital efficiency, that how much return am I likely to get as an investor.

Ashish: I agree with what Tarun has said. For us, it’s a slightly easy job. We come in when the company has been in existence for the last 3-4 years. The input metric that Tarun talks about has been played about, and there is information on what is working and what is not working and there are corrective steps already taken. A lot of times we think about these input metrics but what we have seen in case of good companies is that by the time they spend 3 to 4 years, they have figured out those things.

So what we instead focus on is derivative metrics. These are metrics I talked about such as market share, improving unit economics. The third is the capital element which is a combination of all of this. I will talk about the investments we made in the last few years. One is PharmEasy. When we looked at the entire online pharmacy market space, we were in a tricky situation. Typically, you will find one or two companies broken-out by then. You can make out that they have demonstrated by virtue of their execution that they will likely become the leader. In this case, it was not very clear.

We were looking at five or six companies out of which three of them were very comparable – PharmEasy, NetMeds, and 1mg. When we looked at the two metrics I talked about, we realized we had to look for more input metrics, the kind Tarun spoke about, and we were convinced that there was one company executing far better than others. The second thing we looked at, given that market share had not been fundamentally different at that point of time was, are there accelerators and inputs which can improve the market share for these companies substantially in the next 12 to 18 months? When you look at a country like ours, it is usually whether the customer gets some incentive in the form of a discount or a credit.

It depends upon the servicing customers or businesses, which is one lever for people to accelerate. The second lever we look at is the price element, and that gets in the play very early. So when we come in, given the capital we deploy, we don’t think that has to be a big differentiator. Then there are only two other accelerators we see. One is the brand, and the other one is the network effect. The point now is that if you have already established that your product has value, are there non-price values that you could think of and introduce in your product which can accelerate the growth of the company?

So, in the case of PharmEasy, we found that the network effect is the best accelerator that one can have. In a two-sided marketplace like OLA, if you look at OLA and Uber, they have 90-95% of market share, and if you look at all other existing they couldn’t really sustain that. However, the network effect is not that strong when there is not a strongly two-sided marketplace. Technically Flipkart is a two-sided marketplace, but in reality, it does not play out this way which is why their total market share will be smaller.

All of them put together will probably have 10-15% of it. However, what we saw for PharmEasy was that brand was one thing which could potentially accelerate growth. If you already have good customer experience and product, that is one accelerator which can work, and that was exactly what we used. The TV campaign that ran for the last 6-8 months has helped the company to grow 3x larger than the next competition in the last nine months. That is one testimonial to what we thought would play out and it did. We know that it wouldn’t always play out, but these are the things we consider while investing.

When we looked at TravelTriangle as a business, we spent time on that as well. For TravelTriangle, the competition was a lot trickier. There was a publicly listed very large company, MakeMyTrip. They also had a holiday business, and they invested in a business which was a competition to TravelTriangle. At the same time, there were other competitions which were independent, and they wanted to do something.

We spent time with them as well to find their marketing efficiency and operational efficiency. The third is productivity enhancement to your marketplace stakeholder, which is a travel agent in this case. Is that increasing over a period of time or not? If that is improving, ultimately network effect will start to play out. If the travel agent is becoming more productive because of you, he will start choosing you over anybody else. He will start giving preference and optimize your dealings more than anybody else’s.

That is exactly what we saw play out. We also saw that the competing companies have died except for a few like MakeMyTrip, which continues to be a very large player. We have also found that the market share that TravelTriangle had as compared to MakeMyTrip holiday business has improved. These are a couple of things which fortunately played out well for us.

You explained about product-market-fit and how it varies across segments and industries. For the audience here, can you tell us about one consumer-related sector like e-commerce or content or health and how do you determine if that sector has achieved the product-market-fit?

Ashish: We have publicly written on our website that we only invest in companies which have attained a post-product-market-fit. So, every time there is a conversation; naturally, an entrepreneur comes and asks me what is a product-market-fit. The technical definition of product-market-fit is that there is a market, and your go-to-market defines that there is a need for that market. If you have effectively managed that, you have established a product-market-fit. My understanding has been that these terms have all been coined in the US where the market is reasonably deep.

In a country like us, the market is not deep enough, except probably 2 or 3 industries. The standard definition of product-market-fit does not apply here. In fact, I worry less about product-market-fit and worry more about the market. In general, it is very easy for entrepreneurs to make a mistake- you always do a top-down estimate of the market, and you forget what your product is. At that moment when you do a bottom-up calculation of the market and compare that with the top-down, you will find a significant difference. Usually, we have observed that the bottom number is not more than 10% of the market. So that is one area where we spend a lot of time, primarily also because when we come in, these companies are already valued.

This is why we have to see a significantly larger impact. Any company which cannot become a potentially half a billion dollar company or more, definitely cannot give us a financial result and that is something we won’t participate in. We believe that India is at a place where potentially large companies can be created and there are markets and entrepreneurs which exist that can happen. However, when you talk about, say, a content company, we have been spending a little bit of time there, and I echo what Tarun talked about. There are metrics which can be bought or which can be easily faked such as the daily active and the monthly active. Engagement is a number that we also worry about.

Currently, we are observing two more content companies. One is the content company which is trying to get people like us, which are top 50 or 100 million users in the country. So if you project the country out, say next five or six years, the estimates are that almost 800 million of us will be on the internet doing something and content will be the first thing that people will be consuming. If you break this into the top 50, 100 million and the last 700 million, the GDP per capita for these customers will be fundamentally very different.

The estimate is that at an aggregate level there is 6 to 7-times difference, which means when I look at a company who targets top 50 or 100 million, I worry about the daily active, monthly active, engagement. As analytical people, you know that there is an opportunity to create anywhere between 200 million to 400 million of revenue in a 5-6 years period. So there the metrics for us is the engagement, customer love, and DAU, MAU, but when you talk about last 700 million users, the kind that Chinese usually focus upon, I don’t build a conviction just on engagement metric alone.

That’s when I start worrying about some early signs or direction about how this monetization will begin to happen. Because in the next 5-7 years, I don’t think even at 100-200 million MAU, you will be able to monetize enough to create a large business and a business we want to partner with. For those things, we actually want to see some monetization happening.

Tarun: This reminds me of a board meeting we were in. This is one of the consumer internet e-commerce companies, and this was four years ago. This company was between Series B and Series C, and the founder asked the question do we have the PMF? It was odd the company asked it considering they had already raised three rounds of funding and were growing well. Someone then said that if you are asking this question, you generally don’t have it. That is the way I generally define PMF. I think PMF is not a binary switch but a journey and vs. looking at PMF as this illusory pot of gold that no one can define, I prefer to look at it in three stages.

The first stage is the early PMF; the second is the scalable PMF, and the third is the profitable PMF. The answer becomes a lot more finite and concrete. The other thing I look at, which is more important than PMF, is founder market-fit. Some founders are uniquely more suited to building stop-of-the-stack businesses which have no logistics, no operation on the ground, but are very strong product-tech guys. Then there are others who are not going to belong to the top-of-the-stack businesses; they need to be part of the transaction flow, which are full stack businesses. So, forget the PMF, we spend a lot of time in understanding the founder market-fit.

All these are established industries; I want to get some more sense on coming up in new segments which no one would have thought about before. When it comes to new industries, are there any insights which help you to decide on investing in these new categories?

Tarun: Let me give you an example of scooter-sharing in India, which is relatively a new segment. A lot of companies are starting up, and we have invested in one of them called VOGO. Globally, there is Bird and Lime, etc. The business model in these companies is very different from what an OLA or Uber has. These are aggregation businesses. The metric is the driver’s earning per hour to ensure that the driver remains loyal to a platform. In the case of businesses VOGO, these are self-driven. You basically go from point-to-point and end the ride. These are more of CAPEX, heavy businesses where you buy the hardware and invest in the scooter. Here, the most important metric at the stage we call early PMF is what percentage of your bikes are getting at least one booking a day.

The second metric is of the bikes that are getting one booking, what percentage of them are doing 5-6 rides per day, especially when it is a capex model where you have already invested in leasing that asset, you need to consider those metrics. All the other metrics will come over time example, what is your number of rides, riders, cohorts, gross margin, contribution margin, etc. All these metrics will be similar to other businesses. However, in the early days to know whether there is early PMF coming, these are the two metrics that I have narrowed down to track.

Ashish: I have been a big fan of first principle thinking, and this was before I knew what the term meant. I am extremely bullish in India of people looking at new industries and creating new businesses out of it, and there are macros that support it. One big macro that supports it is that if you look at the country, the number of organized businesses are very little and that is primarily because the effort of starting a business in India has been very difficult. As a result, in the last 40-50 years, organized businesses have not been created which means that for every customer pain, there are 10,000 people who are trying to solve that problem. However, none of them have solved it deep enough that they would be able to take the market share.

If you as an entrepreneur are actually looking at an industry, I will strongly recommend you to go to your customer and live like them and spend some time with them to understand their pain point. Understand it to an extent that you could write it down on one piece of paper rather than 30 pieces of paper. If you are particularly raising venture money, you have to think platform first- what is my go-to-market? What is the product that I can create which can take a higher market share than anybody else has been taking? You cannot be incrementally better.

You will have to think about the customer value proposition that I can create which will ensure that people will use my services more than anybody else’s and I see that opportunity everywhere. I don’t see a lot of people doing platform thinking, but the ones who are doing it will become very large in the coming years.

Thank you, Tarun and Ashish for taking out time to explain to us about the parameters that investors look into while investing in emerging and established consumer internet companies. We believe, everyone must have found these insights valuable for their business.

Here’s what you can read next:

|

![What Investors Look for While Investing in Consumer Internet Companies [#GROWTH19 Wrap-up]](https://www.hashgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Investing-in-Consumer-Internet-Companies.png)